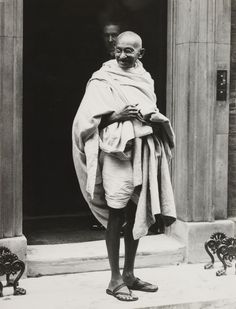

As per our current Database, Ramsay MacDonald has been died on 9 November 1937(1937-11-09) (aged 71)\nAtlantic Ocean, (on holiday aboard the ocean liner Reina del Pacifico).

When Ramsay MacDonald die, Ramsay MacDonald was 71 years old.

| Popular As | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Occupation | Prime Ministers |

| Age | 71 years old |

| Zodiac Sign | Scorpio |

| Born | October 12, 1866 (Lossiemouth, British) |

| Birthday | October 12 |

| Town/City | Lossiemouth, British |

| Nationality | British |

Ramsay MacDonald’s zodiac sign is Scorpio. According to astrologers, Scorpio-born are passionate and assertive people. They are determined and decisive, and will research until they find out the truth. Scorpio is a great leader, always aware of the situation and also features prominently in resourcefulness. Scorpio is a Water sign and lives to experience and express emotions. Although emotions are very important for Scorpio, they manifest them differently than other water signs. In any case, you can be sure that the Scorpio will keep your secrets, whatever they may be.

Ramsay MacDonald was born in the Year of the Tiger. Those born under the Chinese Zodiac sign of the Tiger are authoritative, self-possessed, have strong leadership qualities, are charming, ambitious, courageous, warm-hearted, highly seductive, moody, intense, and they’re ready to pounce at any time. Compatible with Horse or Dog.

...I spent hours of terrible mental pain. Letters of sympathy began to pour in upon me.... Never before did I know that I had been registered under the name of Ramsay, and cannot understand it now. From my earliest years my name has been entered in lists, like the school register, etc. as MacDonald.

MacDonald was born at Gregory Place, Lossiemouth, Morayshire, Scotland, the illegitimate son of John MacDonald, a farm labourer, and Anne Ramsay, a housemaid. Registered at birth as James McDonald (sic) Ramsay, he was known as Jaimie MacDonald. Illegitimacy could be a serious handicap in 19th century Presbyterian Scotland, but in the north and northeast farming communities, this was less of a problem; in 1868, a report of the Royal Commission on the Employment of Children, Young Persons and Women in Agriculture noted that the illegitimacy rate was around 15%, meaning that nearly every sixth person was born out of wedlock. MacDonald's mother had worked as a domestic servant at Claydale farm, near Alves, where his father was also employed. They were to have been married, but the wedding never took place, either because the couple quarrelled and chose not to marry, or because Anne's mother, Isabella Ramsay, stepped in to prevent her daughter from marrying a man she deemed unsuitable.

Ramsay MacDonald received an elementary education at the Free Church of Scotland school in Lossiemouth from 1872 to 1875, and then at Drainie parish school. He left school at the end of the summer term in 1881, at the age of 15, and began work on a nearby farm. In December 1881, he was appointed a pupil Teacher at Drainie parish school. In 1885, he left to take up a position as an assistant to Mordaunt Crofton, a clergyman in Bristol who was attempting to establish a Boys' and Young Men's Guild at St Stephen's Church. It was in Bristol that Ramsay MacDonald joined the Democratic Federation, a Radical organisation. This federation changed its name a few months later to the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). He remained in the group when it left the SDF to become the Bristol Socialist Society. In early 1886 he moved to London.

Politics in the 1880s was still of less importance to MacDonald than furthering his education. He took evening classes in science, botany, agriculture, mathematics, and physics at the Birkbeck Literary and Scientific Institution but his health suddenly failed him due to exhaustion one week before his examinations. This put an end to any thought of a scientific career. In 1888, MacDonald took employment as private secretary to Thomas Lough who was a tea merchant and a Radical Politician. Lough was elected as the Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) for West Islington, in 1892. Many doors now opened to MacDonald: he had access to the National Liberal Club as well as the editorial offices of Liberal and Radical newspapers; he made himself known to various London Radical clubs among Radical and labour politicians. MacDonald gained valuable experience in the workings of electioneering. At the same time he left Lough's employment to branch out as a freelance Journalist. Elsewhere as a member of the Fabian Society for some time, MacDonald toured and lectured on its behalf at the London School of Economics and elsewhere.

The Trades Union Congress had created the Labour Electoral Association (LEA) and entered into an unsatisfactory alliance with the Liberal Party in 1886. In 1892, MacDonald was in Dover to give support to the candidate for the LEA in the General Election who was well beaten. MacDonald impressed the local press and the Association and was adopted as its candidate, announcing that his candidature would be under a Labour Party banner. He denied the Labour Party was a wing of the Liberal Party but saw merit in a working political relationship. In May 1894, the local Southampton Liberal Association was trying to find a labour-minded candidate for the constituency. Two others joined MacDonald to address the Liberal Council: one was offered but turned down the invitation, while MacDonald failed to secure the nomination despite strong support among Liberals.

Following a short period of work addressing envelopes at the National Cyclists' Union in Fleet Street, he found himself unemployed and forced to live on the small amount of money he had saved from his time in Bristol. MacDonald eventually found employment as an invoice clerk in the warehouse of Cooper, Box and Co. During this time he was deepening his socialist credentials, and engaged himself energetically in C. L. Fitzgerald's Socialist Union which, unlike the SDF, aimed to progress socialist ideals through the parliamentary system. MacDonald witnessed the Bloody Sunday of 13 November 1887 in Trafalgar Square, and in response, had a pamphlet published by the Pall Mall Gazette, entitled Remember Trafalgar Square: Tory Terrorism in 1887.

MacDonald retained an interest in Scottish politics. Gladstone's first Irish Home Rule Bill inspired the setting-up of a Scottish Home Rule Association in Edinburgh. On 6 March 1888, MacDonald took part in a meeting of London-based Scots, who, upon his motion, formed the London General Committee of Scottish Home Rule Association. For a while he supported home rule for Scotland, but found little support among London's Scots. However, MacDonald never lost his interest in Scottish politics and home rule, in Socialism: critical and constructive, published in 1921, he wrote: "The Anglification of Scotland has been proceeding apace to the damage of its education, its music, its literature, its genius, and the generation that is growing up under this influence is uprooted from its past."

In 1893, Keir Hardie had formed the Independent Labour Party (ILP) which had established itself as a mass movement. In May 1894 MacDonald applied for membership, and was accepted. He was officially adopted as the ILP candidate for one of the Southampton seats on 17 July 1894 but was heavily defeated at the election of 1895. MacDonald stood for Parliament again in 1900 for one of the two Leicester seats and although he lost was generously accused of splitting the Liberal vote to allow the Conservative candidate to win. That same year he became Secretary of the Labour Representation Committee (LRC), the forerunner of the Labour Party, allegedly in part because many delegates confused him with prominent London trade unionist Jimmie MacDonald when they voted for "Mr. James R. MacDonald". MacDonald retained membership of the ILP; while it was not a Marxist organisation it was more rigorously socialist than the once and Future Labour Party in which the ILP members would operate as a "ginger group" for many years.

Ramsay MacDonald married Margaret Ethel Gladstone (no relation to 19th-century Prime Minister william Gladstone) in 1896. The marriage was a very happy one, and they had six children, including Malcolm MacDonald (1901–81), who had a distinguished career as a Politician, colonial governor and diplomat, and Ishbel MacDonald (1903–82), who was very close to her father. Another son, Alister Gladstone MacDonald (1898–1993) was a conscientious objector in the First World War, serving in the Friends' Ambulance Unit; he became a prominent Architect who worked on promoting the planning policies of his father's government, and specialised in cinema design. MacDonald was devastated by Margaret's death from blood poisoning in 1911, and had few significant personal relationships after that time, apart from with Ishbel, who cared for him for the rest of his life. Following his wife's death, MacDonald commenced a relationship with Lady Margaret Sackville.

It was during this period that MacDonald and his wife began a long friendship with the social investigator and reforming civil servant Clara Collet with whom he discussed women's issues. She was an influence on MacDonald and other politicians in their attitudes towards women rights. In 1901, he was elected to the London County Council for Finsbury Central as a joint Labour–Progressive Party candidate, but he was disqualified from the register in 1904 due to his absences abroad.

In 1906, the LRC changed its name to the "Labour Party", amalgamating with the ILP. In that same year, MacDonald was elected MP for Leicester along with 28 others, and became one of the Leaders of the Parliamentary Labour Party. These Labour MPs undoubtedly owed their election to the 'Progressive Alliance' between the Liberals and Labour, a minor party supporting the Liberal governments of Henry Campbell-Bannerman and H. H. Asquith. MacDonald became the leader of the left wing of the party, arguing that Labour must seek to displace the Liberals as the main party of the left.

In 1911 MacDonald became Party Leader (formally "Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party"). He was the chief intellectual leader of the party, paying little attention to class warfare and much more to the emergence of a powerful state as it exemplified the Darwinian evolution of an ever more complex society. He was an Orthodox Edwardian progressive, keen on intellectual discussion, and adverse to agitation.

MacDonald had long been a leading spokesman for internationalism in the Labour movement; at first he verged on pacifism. He founded the Union of Democratic Control in early 1914 to promote international socialist aims, but it was overwhelmed by the war. His 1916 book, National Defence, revealed his own long-term vision for peace. Although disappointed at the harsh terms of the Versailles Treaty, he supported the League of Nations – but by 1930 he felt that the internal cohesion of the British Empire and a strong, independent British defence programme might turn out to be the wisest British government policy.

MacDonald's unpopularity in the country following his stance against Britain's involvement in the First World War spilled over into his private life. In 1916, he was expelled from Moray Golf Club in Lossiemouth for supposedly bringing the club into disrepute because of his pacifist views. The manner of his expulsion was regretted by some members but an attempt to re-instate him by a vote in 1924 failed. However, a Special General Meeting held in 1929 finally voted for his reinstatement. By this time, MacDonald was Prime Minister for the second time. He felt the initial expulsion very deeply and refused to take up the final offer of membership.

As the war dragged on, his reputation recovered but he still lost his seat in the 1918 "Coupon Election", which saw the Liberal David Lloyd George's coalition government win a large majority.

MacDonald had never held office but demonstrated Energy, executive ability, and political astuteness. He consulted widely within his party, making the Liberal Lord Haldane the Lord Chancellor, and Philip Snowden Chancellor of the Exchequer. He took the foreign office himself. Besides himself, ten other cabinet members came from working class origins, a dramatic breakthrough in British history. His first priority was to undo the perceived damage caused by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, by settling the reparations issue and coming to terms with Germany. The king noted in his diary, "He wishes to do the right thing.... Today 23 years ago dear Grandmama died. I wonder what she would have thought of a Labour Government!"

In the 1920s and 1930s he was frequently entertained by the society hostess Lady Londonderry, which was much disapproved of in the Labour Party since her husband was a Conservative cabinet minister.

MacDonald stood for Parliament in the 1921 Woolwich East by-election and lost. In 1922, MacDonald was returned to the House as MP for Aberavon in Wales, With a vote of 14,318 against 11,111 and 5,328 for his main opponents. His rehabilitation was complete; the Labour New Leader magazine opined that his election was, "enough in itself to transform our position in the House. We have once more a voice which must be heard."

At the 1922 election, Labour replaced the Liberals as the main opposition party to the Conservative government of Stanley Baldwin, making MacDonald Leader of the Opposition. By now, he had moved away from the Labour left and abandoned the socialism of his youth: he strongly opposed the wave of radicalism that swept through the labour movement in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and became a determined enemy of Communism. Unlike the French Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party of Germany, the Labour Party did not split and the Communist Party of Great Britain remained small and isolated.

At the 1923 election, the Conservatives had lost their majority, and when they lost a vote of confidence in the House in January 1924 King George V called on MacDonald to form a minority Labour government, with the tacit support of the Liberals under Asquith from the corner benches. He became the first Labour Prime Minister, the first from a working class background and one of the very few without a university education.

On 25 October 1924, just four days before the election, the Daily Mail reported that a letter had come into its possession which purported to be a letter sent from Grigory Zinoviev, the President of the Communist International, to the British representative on the Comintern Executive. The letter was dated 15 September and so before the dissolution of parliament; it stated that it was imperative for the agreed treaties between Britain and the Bolsheviks to be ratified urgently. The letter said that those Labour members who could apply pressure on the government should do so. It went on to say that a resolution of the relationship between the two countries would "assist in the revolutionising of the international and British proletariat ... make it possible for us to extend and develop the ideas of Leninism in England and the Colonies". The government had received the letter before the publication in the newspapers and had protested to the Bolsheviks' London chargé d'affaires and had already decided to make public the contents of the letter with details of the official protest but had not been swift-footed enough. Historians mostly agree the letter was a forgery, but it closely reflected attitudes current in the Comintern. In any case, it had little impact on the Labour vote, which actually increased. It was the collapse of the Liberal Party that led to the Conservative landslide. However, many Labourites for years blamed their defeat on the Letter by misunderstanding the political forces at work. Despite all that had gone on, the result of the election was not disastrous for Labour. The Conservatives were returned decisively gaining 155 seats for a total of 413 members of parliament. Labour lost 40 seats but held on to 151. The Liberals lost 118 seats (leaving them with only 40) and their vote fell by over a million. The real significance of the election was that the Liberals, whom Labour had displaced as the second largest political party in 1922, were now clearly the third party.

Scholarly analysis about the economic decisions taken in the inter-war period such as the return to the Gold Standard in 1925, and MacDonald's desperate efforts to defend it in 1931, has changed. Robert Skidelsky, in his classic account of the 1929–31 government, Politicians and the Slump (1967), compared the orthodox policies advocated by leading politicians of both parties unfavourably with the more radical, proto-Keynesian measures proposed by David Lloyd George and Oswald Mosley. But in the preface to the 1994 edition Skidelsky argued that recent experience of currency crises and capital FLIGHT made it hard to be critical of politicians who wanted to achieve stability by cutting labour costs and defending the value of the currency. In 2004 Marquand advanced a similar argument:

The strong majority held by the Conservatives gave Baldwin a full term during which the government had to deal with the 1926 General Strike. Unemployment remained high but relatively stable at just over 10% and, apart from 1926, strikes were at a low level. At the May 1929 election, Labour won 288 seats to the Conservatives' 260, with 59 Liberals under Lloyd George holding the balance of power. MacDonald was increasingly out of touch with his supposedly safe Welsh seat at Aberavon; he largely ignored the district, and had little time or Energy to help with its increasingly difficult problems regarding coal disputes, strikes, unemployment and poverty. The miners expected a wealthy man who would fund party operations, but he had no money. He disagreed with the increasingly radical activism of party Leaders in the district, as well as the permanent agent, and the South Wales Mineworkers' Federation. He moved to Seaham Harbour in County Durham, a safer seat, in order to avoid a highly embarrassing defeat.

MacDonald's government had no effective response to the economic crisis which followed the Stock Market Crash of 1929. Philip Snowden was a rigid exponent of orthodox Finance and would not permit any deficit spending to stimulate the economy, despite the urgings of Oswald Mosley, David Lloyd George and the Economist John Maynard Keynes. Mosley put forward a memorandum in January 1930, calling for the public control of imports and banking as well as an increase in pensions to boost spending power. When this was repeatedly turned down, Mosley resigned from the government in February 1931 and formed the New Party. He later converted to Fascism.

By the end of 1930, unemployment had doubled to over two and a half million. The government struggled to cope with the crisis and found itself attempting to reconcile two contradictory aims: achieving a balanced budget to maintain the pound on the Gold standard, and maintaining assistance to the poor and unemployed, at a time when tax revenues were falling. During 1931 the economic situation deteriorated, and pressure from orthodox economists for sharp cuts in government spending increased. Under pressure from its Liberal allies as well as the Conservative opposition who feared that the budget was unbalanced, Snowden appointed a committee headed by Sir George May to review the state of public finances. The May Report of July 1931 urged large public-sector wage cuts and large cuts in public spending (notably in payments to the unemployed) to avoid a budget deficit.

MacDonald's expulsion from Labour along with his National Labour Party's coalition with the Conservatives, combined with the decline in his physical and mental powers after 1931, left him a discredited figure at the time of his death, destined to receive years of unsympathetic treatment from generations of Labour-inclined British historians. The events of 1931, with the downfall of the Labour government and his coalition with the Conservatives, led to MacDonald becoming one of the most reviled figures in the history of the Labour Party, with many of his former supporters accusing him of betraying the party he had helped create. Lachlan MacNeill Weir, MacDonald's former parliamentary private secretary, published the first major biography The Tragedy of Ramsay MacDonald in 1938. Weir demonised MacDonald for obnoxious careerism, class betrayal and treachery. Clement Attlee in his autobiography As it Happened (1954) called MacDonald's decision to abandon the Labour government in 1931 "the greatest betrayal in the political history of the country". The coming of war in 1939 led to a search for the politicians who had appeased Hitler and failed to prepare Britain; MacDonald was grouped among the "Guilty Men".

MacDonald was deeply affected by the anger and bitterness caused by the fall of the Labour government. He continued to regard himself as a true Labour man, but the rupturing of virtually all his old friendships left him an isolated figure. One of the only other leading Labour figures to join the government, Philip Snowden, was a firm believer in free trade and resigned from the government in 1932 following the introduction of tariffs after the Ottawa agreement.

By 1933 MacDonald's health was so poor that his Doctor had to personally supervise his trip to Geneva. By 1934 MacDonald's mental and physical health declined further, and he became an increasingly ineffective leader as the international situation grew more threatening. His speeches in Commons and at international meetings became incoherent. One observer noted how "Things ... got to the stage where nobody knew what the Prime Minister was going to say in the House of Commons, and, when he did say it, nobody understood it". Newspapers did not report MacDonald denying to reporters that he was seriously ill because he only had "loss of memory". His pacifism, which had been widely admired in the 1920s, led Winston Churchill and others to accuse him of failure to stand up to the threat of Adolf Hitler. His government began the negotiations for the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. MacDonald was aware of his fading powers, and in 1935 he agreed to a timetable with Baldwin to stand down as Prime Minister after George V's Silver Jubilee celebrations in May 1935. He resigned on 7 June in favour of Baldwin, and remained in the cabinet, taking the largely honorary post of Lord President vacated by Baldwin.

At the 1935 election MacDonald was defeated at Seaham by Emanuel Shinwell. Shortly after he was elected at a by-election in January 1936 for the Combined Scottish Universities seat, but his physical and mental health collapsed in 1936. King George V died a week before voting began in the Scottish by-election and MacDonald deeply mourned his death, paying tribute to him in his diary as "a gracious and kingly friend whom I have served with all my heart". There had been a genuine mutual affection between the two; the King is said to have regarded MacDonald as his favourite prime minister.

After Hitler's re-militarisation of the Rhineland in 1936, MacDonald declared that he was "pleased" that the Treaty of Versailles was "vanishing", expressing his hope that the French had been taught a "severe lesson".

A sea voyage was recommended to restore MacDonald's health, but he died on board the liner MV Reina del Pacifico at sea on 9 November 1937, aged 71 when with his youngest daughter Sheila. His funeral was in Westminster Abbey on 26 November. After cremation, his ashes were buried alongside his wife Margaret at Spynie in his native Morayshire.

By the 1960s, while union Activists maintained their hostile attitude, scholars wrote with more appreciation of his challenges and successes. Finally in 1977 he received a long scholarly biography that historians have judged to be "definitive." Labour MP David Marquand, a trained Historian who later became a professor of politics, wrote Ramsay MacDonald with the stated intention of giving MacDonald his due for his work in founding and building the Labour Party, and in trying to preserve peace in the years between the two world wars. He argued also to place MacDonald's fateful decision in 1931 in the context of the crisis of the times and the limited choices open to him. Marquand praised the prime minister's decision to place national interests before that of party in 1931. He also emphasised MacDonald's lasting intellectual contribution to socialism and his pivotal role in transforming Labour from an outside protest group to an inside party of government.