As per our current Database, John Ruskin has been died on 20 January 1900(1900-01-20) (aged 80)\nBrantwood, Coniston, England.

When John Ruskin die, John Ruskin was 80 years old.

| Popular As | John Ruskin |

| Occupation | Writers |

| Age | 80 years old |

| Zodiac Sign | Pisces |

| Born | February 08, 1819 (England, British) |

| Birthday | February 08 |

| Town/City | England, British |

| Nationality | British |

John Ruskin’s zodiac sign is Pisces. According to astrologers, Pisces are very friendly, so they often find themselves in a company of very different people. Pisces are selfless, they are always willing to help others, without hoping to get anything back. Pisces is a Water sign and as such this zodiac sign is characterized by empathy and expressed emotional capacity.

John Ruskin was born in the Year of the Rabbit. Those born under the Chinese Zodiac sign of the Rabbit enjoy being surrounded by family and friends. They’re popular, compassionate, sincere, and they like to avoid conflict and are sometimes seen as pushovers. Rabbits enjoy home and entertaining at home. Compatible with Goat or Pig.

We want one man to be always thinking, and another to be always working, and we call one a gentleman, and the other an operative; whereas the workman ought often to be thinking, and the thinker often to be working, and both should be gentlemen, in the best sense. As it is, we make both ungentle, the one envying, the other despising, his brother; and the mass of society is made up of morbid thinkers and miserable workers. Now it is only by labour that thought can be made healthy, and only by thought that labour can be made happy, and the two cannot be separated with impunity.

— John Ruskin, Cook and Wedderburn 10.201.

Millais had painted Effie for The Order of Release, 1746, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852. Suffering increasingly from physical illness and acute mental anxiety, Effie was arguing fiercely with her husband and his intense and overly protective parents, and seeking solace with her own parents in Scotland. The Ruskin marriage was already fatally undermined as she and Millais fell in love, and Effie left Ruskin, causing a public scandal.

Ruskin was the only child of first cousins. His father, John James Ruskin, (1785–1864), was a sherry and wine importer, founding partner and de facto Business manager of Ruskin, Telford and Domecq (see Allied Domecq). John James was born and brought up in Edinburgh, Scotland, to a mother from Glenluce and a father originally from Hertfordshire. His wife, Margaret Cox, née Cock (1781–1871), was the daughter of an aunt on the English side of the family and a publican in Croydon. She had joined the Ruskin household when she became companion to John James's mother, Catherine.

Before he returned, he answered a challenge set down by Effie Gray, whom he later married. The twelve-year-old Effie had asked him to write a fairy story. During a six-week break at Leamington Spa to undergo Dr. Jephson's (1798–1878) celebrated salt-water cure, Ruskin wrote his only work of fiction, the fairy tale, The King of the Golden River (published in December 1850 (but imprinted 1851) with illustrations by Richard Doyle). A work of Christian sacrificial morality and charity, it is set in the Alpine landscape Ruskin loved and knew so well. It remains the most translated of all his works. At Oxford, he sat for a pass degree in 1842, and was awarded with an uncommon honorary double fourth-class degree in recognition of his achievements.

Ruskin's childhood was spent from 1823 at 28 Herne Hill (demolished c. 1912), near the village of Camberwell in South London. It was not the friendless and toyless experience he later claimed in his autobiography, Praeterita (1885–89). He was educated at home by his parents and private tutors, and from 1834 to 1835 attended the school in Peckham run by the progressive Evangelical, Thomas Dale (1797–1870). Ruskin heard Dale lecture in 1836 at King's College, London, where Dale was the first Professor of English Literature. Ruskin went on to enroll and complete his studies at King's College, where he prepared for Oxford under Dale's tutelage.

Ruskin's journeys also provided inspiration for writing. His first publication was the poem "On Skiddaw and Derwent Water" (originally entitled Lines written at the Lakes in Cumberland: Derwentwater and published in the Spiritual Times) (August 1829). In 1834 three short articles for Loudon's Magazine of Natural History were published. They show early signs of his skill as a close "scientific" observer of nature, especially its geology.

The tours provided Ruskin with the opportunity to observe and to record his impressions of nature. He composed elegant if largely conventional poetry, some of which was published in Friendship's Offering. His early notebooks and sketchbooks are full of visually sophisticated and technically accomplished drawings of maps, landscapes and buildings, remarkable for a boy of his age. He was profoundly affected by a copy of Samuel Rogers's poem, Italy (1830), which was given to him as a 13th birthday present. In particular, he admired deeply the accompanying illustrations by J. M. W. Turner, and much of his art in the 1830s was in imitation of Turner, and Samuel Prout whose Sketches Made in Flanders and Germany (1833) he also admired. His artistic skills were refined under the tutelage of Charles Runciman, Copley Fielding and James Duffield Harding. Gradually, he abandoned his picturesque style in favour of naturalism.

In Michaelmas 1836, Ruskin matriculated at the University of Oxford, taking up residence at Christ Church in January of the following year. Enrolled as a gentleman-commoner, he enjoyed equal status with his aristocratic peers. His study of classical "Greats" might, his parents hoped, lead him to take Holy Orders and become a bishop, perhaps even the Archbishop of Canterbury. Ruskin was generally uninspired by Oxford and suffered bouts of illness. Perhaps the keenest advantage of his time in residence was found in the few, close friendships he made. His tutor, the Rev Walter Lucas Brown, was always encouraging, as was a young senior tutor, Henry Liddell (later the father of Alice Liddell) and a private tutor, the Rev Osborne Gordon. He became close to the Geologist and natural theologian, william Buckland. Among Ruskin's fellow undergraduates, the most important friends were Charles Thomas Newton and Henry Acland.

From September 1837 to December 1838, Ruskin's The Poetry of Architecture was serialised in Loudon's Architectural Magazine, under the pen name "Kata Physin" (Greek for "According to Nature"). It was a study of cottages, villas, and other dwellings which centred on a Wordsworthian argument that buildings should be sympathetic to their immediate environment and use local materials, and anticipated key themes in his later writings. In 1839, Ruskin's 'Remarks on the Present State of Meteorological Science' was published in Transactions of the Meteorological Society.

Before Ruskin began Modern Painters, John James Ruskin had begun collecting watercolours, including works by Samuel Prout and, from 1839, Turner. Both Painters were among occasional guests of the Ruskins at Herne Hill, and 163 Denmark Hill (demolished 1947) to which the family moved in 1842.

Much of the period, from late 1840 to autumn 1842, Ruskin spent abroad with his parents, principally in Italy. His studies of Italian art were chiefly guided by George Richmond, to whom the Ruskins were introduced by Joseph Severn, a friend of Keats (whose son, Arthur Severn, married Ruskin's cousin, Joan). He was galvanised into writing a defence of J. M. W. Turner when he read an attack on several of Turner's pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy. It recalled an attack by critic, Rev John Eagles, in Blackwood's Magazine in 1836, which had prompted Ruskin to write a long essay. John James had sent the piece to Turner who did not wish it to be published. It finally appeared in 1903.

What became the first volume of Modern Painters (1843), published by Smith, Elder & Co. under the anonymous but authoritative title, "A Graduate of Oxford," was Ruskin's response to Turner's critics. An electronic edition is available online. Ruskin controversially argued that modern landscape painters—and in particular Turner—were superior to the so-called "Old Masters" of the post-Renaissance period. Ruskin maintained that Old Masters such as Gaspard Dughet (Gaspar Poussin), Claude, and Salvator Rosa, unlike Turner, favoured pictorial convention, and not "truth to nature". He explained that he meant "moral as well as material truth". The job of the Artist is to observe the reality of nature and not to invent it in a studio—to render what he has seen and understood imaginatively on canvas, free of any rules of composition. For Ruskin, modern landscapists demonstrated superior understanding of the "truths" of water, air, clouds, stones, and vegetation, a profound appreciation of which Ruskin demonstrated in his own prose. He described works he had seen at the National Gallery and Dulwich Picture Gallery with extraordinary Verbal felicity.

Ruskin toured the continent again with his parents in 1844, visiting Chamonix and Paris, studying the geology of the Alps and the paintings of Titian, Veronese and Perugino among others at the Louvre. In 1845, at the age of 26, he undertook to travel without his parents for the first time. It provided him with an opportunity to study medieval art and architecture in France, Switzerland and especially Italy. In Lucca he saw the Tomb of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia which Ruskin considered the exemplar of Christian sculpture (he later associated it with the object of his love, Rose La Touche). He drew inspiration from what he saw at the Campo Santo in Pisa, and in Florence. He was particularly impressed by the works of Fra Angelico and Giotto in San Marco, and Tintoretto in the Scuola di San Rocco but was alarmed by the combined effects of decay and modernisation on Venice: "Venice is lost to me," he wrote. It crystallised his lifelong conviction that to restore was to destroy, and that the only true course was preservation and conservation.

Drawing on his travels, he wrote the second volume of Modern Painters (published April 1846). The volume concentrated more on Renaissance and pre-Renaissance artists than on Turner. It was a more theoretical work than its predecessor. Ruskin explicitly linked the aesthetic and the Divine, arguing that truth, beauty and religion are inextricably bound together: "the Beautiful as a gift of God". In defining categories of beauty and imagination, Ruskin argued all great artists must perceive beauty and, with their imagination, communicate it creatively through symbols. Generally, critics gave this second volume a warmer reception although many found the attack on the aesthetic orthodoxy associated with Sir Joshua Reynolds difficult to take. In the summer, Ruskin was abroad again with his father who still hoped his son might become a poet, even poet laureate just one among many factors increasing the tension between them.

John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti had established the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. The Pre-Raphaelite commitment to 'naturalism' – "paint[ing] from nature only", depicting nature in fine detail, had been influenced by Ruskin.

Ruskin's belief in preservation of ancient buildings had a significant influence on later thinking about the distinction between conservation and restoration. Ruskin was a strong proponent of the former, while his contemporary, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, promoted the latter. In The Seven Lamps of Architecture, (1849) Ruskin wrote:

Ruskin attacked orthodox, 19th-century political economy principally on the grounds that it failed to acknowledge complexities of human desires and motivations (broadly, "social affections"). He began to express such ideas in The Stones of Venice, and increasingly in works of the later 1850s, such as The Political Economy of Art (A Joy For Ever), but he gave them full expression in the influential essays, Unto This Last.

Ruskin had been in Venice when he heard about Turner's death in 1851. Named an executor to Turner's will, it was an honour that Ruskin respectfully declined, but later took up. In 1856 Ruskin's book in celebration of the sea, The Harbours of England, revolving around Turner's drawings, was published. In January 1857, Ruskin's Notes on the Turner Gallery at Marlborough House, 1856 was published. He persuaded the National Gallery to allow him to work on the Turner Bequest of nearly 20,000 individual art-works left to the nation by the Artist. This involved Ruskin in an enormous amount of work, completed in May 1858: cataloguing, framing and conserving. 400 watercolours were displayed in cabinets of Ruskin's design. Recent scholarship has argued that Ruskin did not, as previously thought, collude in the destruction of Turner's erotic drawings, but his work on the Bequest did modify his attitude towards Turner. (See below, Controversies: Turner’s Erotic Drawings)

Ruskin's theories also inspired some Architects to adapt the Gothic style. Such buildings created what has been called a distinctive "Ruskinian Gothic". Through his friendship with Sir Henry Acland, from 1854 Ruskin supported attempts to establish what became the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (designed by Benjamin Woodward) which is the closest thing to a model of this style, but still failed completely to satisfy Ruskin. The many twists and turns in the Museum's development, not least its increasing cost, and the University authorities' less than enthusiastic attitude towards it, proved increasingly frustrating for Ruskin.

Ruskin continued to support Hunt and Rossetti. He also provided an annuity of £150 in 1855–57 to Elizabeth Siddal, Rossetti's wife, to encourage her art (and paid for the services of Henry Acland for her medical care). Other artists influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites also received both critical and financial support from Ruskin, including John Brett, John william Inchbold, and Edward Burne-Jones who became a good friend (he called him "Brother Ned"). His father's disapproval of such friends was a further cause of considerable tension between them.

Both volumes III and IV of Modern Painters were published in 1856. In MP III Ruskin argued that all great art is "the expression of the spirits of great men". Only the morally and spiritually healthy are capable of admiring the noble and the beautiful, and transforming them into great art by imaginatively penetrating their essence. MP IV presents the geology of the Alps in terms of landscape painting, and its moral and spiritual influence on those living nearby. The contrasting final chapters, "The Mountain Glory" and "The Mountain Gloom" provide an early Example of Ruskin’s social analysis, highlighting the poverty of the peasants living in the lower Alps.

Many streets, buildings, organisations and institutions bear his name. The Priory Ruskin Academy in Grantham, Lincolnshire, Anglia Ruskin University in Chelmsford and Cambridge traces its origins to the Cambridge School of Art, at the foundation of which Ruskin spoke in 1858. John Ruskin College, South Croydon, is named after him. The Ruskin Literary and Debating Society, (founded in 1900 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada), the oldest surviving club of its type, still promoting the development of literary knowledge and public speaking today. The Ruskin Art Club is the oldest ladies club in Los Angeles. In addition, there is the Ruskin Pottery, Ruskin House, Croydon and Ruskin Hall at the University of Pittsburgh.

From 1859 until 1868, Ruskin was involved with the progressive school for girls at Winnington Hall in Cheshire. A frequent visitor, letter-writer, and donor of pictures and geological specimens, Ruskin approved of the mixture of Sports, handicrafts, music and dancing embraced by its principal, Miss Bell. The association led to Ruskin's sub-Socratic work, The Ethics of the Dust (published December 1865, imprinted 1866), an imagined conversation with Winnington girls in which he cast himself as the "Old Lecturer". On the surface a discourse on crystallography, it represents a metaphorical exploration of social and political ideals. In the 1880s, Ruskin became involved with another educational institution, Whitelands College, a training college for teachers, where he instituted a May Queen festival that endures today. (It was also replicated in the 19th century at the Cork High School for Girls.)

Ruskin lectured widely in the 1860s, giving the Rede lecture at the University of Cambridge in 1867, for Example. He spoke at the British Institution on 'Modern Art', the Working Men's Institute, Camberwell on "Work" and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich on 'War'. Ruskin's widely admired lecture, Traffic, on the relations of taste and morality, was delivered in April 1864 at Bradford Town Hall, to which he had been invited because of a local debate about the style of a new Exchange building. "I do not care about this Exchange," Ruskin told his audience, "because you don't!" These last three lectures were published in The Crown of Wild Olive (1866).

Ruskin was an art-philanthropist: in March 1861 he gave 48 Turner drawings to the Ashmolean in Oxford, and a further 25 to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge in May. Ruskin's own work was very distinctive, and he occasionally exhibited his watercolours: in the United States in 1857–58 and 1879, for example; and in England, at the Fine Art Society in 1878, and at the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolour (of which he was an honorary member) in 1879. He created many careful studies of natural forms, based on his detailed botanical, geological and architectural observations. Examples of his work include a painted, floral pilaster decoration in the central room of Wallington Hall in Northumberland, home of his friend Pauline Trevelyan. The stained glass window in the Little Church of St Francis Funtley, Fareham, Hampshire is reputed to have been designed by him. Originally placed in the St. Peter's Church Duntisbourne Abbots near Cirencester, the window depicts the Ascension and the Nativity.

In the preface to Unto This Last (1862), Ruskin recommended that the state should underwrite standards of Service and production to guarantee social justice. This included the recommendation of government youth-training schools promoting employment, health, and 'gentleness and justice'; government manufactories and workshops; government schools for the employment at fixed wages of the unemployed, with idlers compelled to toil; and pensions provided for the elderly and the destitute, as a matter of right, received honourably and not in shame. Many of these ideas were later incorporated into the welfare state.

Ruskin's sense of politics was not confined to theory. On his father's death in 1864, Ruskin inherited a considerable fortune of between £120,000 and £157,000 (the exact figure is disputed). This considerable inheritance from the father he described on his tombstone as "an entirely honest merchant" gave him the means to engage in personal philanthropy and practical schemes of social amelioration. One of his first actions was to support the housing work of Octavia Hill (originally one of his art pupils), by buying property in Marylebone for her philanthropic housing scheme. But Ruskin's endeavours extended to a shop selling pure tea in any quantity desired at 29 Paddington Street, Paddington (giving employment to two former Ruskin family servants) and crossing-sweepings to keep the area around the British Museum clean and tidy. Modest as these practical schemes were, they represented a symbolic challenge to the existing state of society. Yet his greatest practical experiments would come in his later years.

The lectures that comprised Sesame and Lilies (published 1865), delivered in December 1864 at the town halls at Rusholme and Manchester, are essentially concerned with education and ideal conduct. "Of Kings' Treasuries" (in support of a library fund) explored issues of reading practice, literature (books of the hour vs. books of all time), cultural value and public education. "Of Queens' Gardens" (supporting a school fund) focused on the role of women, asserting their rights and duties in education, according them responsibility for the household and, by extension, for providing the human compassion that must balance a social order dominated by men. This book proved to be one of Ruskin's most popular books, and was regularly awarded as a Sunday School prize. The book's reception over time, however, has been more mixed, and twentieth-century feminists have taken aim at "Of Queens' Gardens" particularly as an effort to "subvert the new heresy" of women's rights by confining women to the domestic sphere.

Ruskin was unanimously appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University in August 1869, largely through the offices of his friend, Henry Acland. He delivered his inaugural lecture on his 51st birthday in 1870, at the Sheldonian Theatre to a larger-than-expected audience. It was here that he said, "The art of any country is the exponent of its social and political virtues.". Thus, its effect on each man should be visible and moving. Cecil Rhodes cherished a long-hand copy of the lecture, believing that it supported his own view of the British Empire.

Ruskin continued to travel, studying the landscapes, buildings and art of Europe. In May 1870 and June 1872 he admired Carpaccio's St Ursula in Venice, a vision of which, associated with Rose La Touche would haunt him, described in the pages of Fors. In 1874, on his tour of Italy, Ruskin visited Sicily, the furthest he ever travelled.

In August 1871, Ruskin purchased from W. J. Linton the then somewhat dilapidated Brantwood, on the shores of Coniston Water, in the English Lake District, paying £1500. It remains open to visitors today. It was Ruskin's main home from 1872 until his death. His estate provided a site for more of his practical schemes and experiments: an ice house was built, the gardens were comprehensively rearranged, he oversaw the construction of a larger harbour (from where he rowed his boat, the Jumping Jenny), and altered the house (adding a dining room, turret to his bedroom to give a panoramic view of the lake, and later expanding further to accommodate his relatives). He built a reservoir, and redirected the waterfall down the hills, adding a slate seat that faced the tumbling stream rather than the lake, so that he could closely observe the fauna and flora of the hillside.

Most controversial, from the point of view of the University authorities, spectators and the national press, was the digging scheme on Ferry Hinksey Road at North Hinksey, near Oxford, instigated by Ruskin in 1874, and continuing into 1875, which involved undergraduates in a road-mending scheme. Motivated in part by a Desire to teach the virtues of wholesome manual labour, some of the diggers, which included Oscar Wilde, Alfred Milner and Ruskin's Future secretary and biographer, W. G. Collingwood, were profoundly influenced by the experience—notably Arnold Toynbee, Leonard Montefiore and Alexander Robertson MacEwen. It helped to foster a public Service ethic that was later given expression in the university settlements, and was keenly celebrated by the founders of Ruskin Hall, Oxford.

Ruskin had been introduced to the wealthy Irish La Touche family by Louisa, Marchioness of Waterford. Maria La Touche, a minor Irish poet and Novelist, asked Ruskin to teach her daughters drawing and painting in 1858. Rose La Touche was ten, Ruskin nearly 39. Ruskin gradually fell in love with her. Their first meeting came at a time when Ruskin's own religious faith was under strain. This always caused difficulties for the staunchly Protestant La Touche family who at various times prevented the two from meeting. Ruskin's love for Rose was a cause alternately of great joy and deep depression for him, and always a source of anxiety. Ruskin proposed to her on or near her eighteenth birthday in 1867, but she asked him to wait three years for an answer, until she was 21. A chance meeting at the Royal Academy in 1869 was one of the few occasions they came into personal contact thereafter. She finally rejected him in 1872, but they still occasionally met, for the final time on 15 February 1875. After a long illness, she died on 25 May 1875, at the age of 27. These events plunged Ruskin into despair and led to increasingly severe bouts of mental illness involving a number of breakdowns and delirious visions. The first of these had occurred in 1871 at Matlock, Derbyshire, a town and a county that he knew from his boyhood travels, whose flora, fauna, and minerals helped to form and reinforce his appreciation and understanding of nature. Ruskin turned to spiritualism and was by turns comforted and disturbed by what he believed was his ability to communicate with the dead Rose.

In the July 1877 letter of Fors Clavigera, Ruskin launched a scathing attack on paintings by James McNeill Whistler exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery. He found particular fault with Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, and accused Whistler of "ask[ing] two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face". Whistler filed a libel suit against Ruskin. Whistler won the case, which went to trial in Ruskin's absence in 1878 (he was ill), but the jury awarded damages of only one farthing to the Artist. Court costs were split between both parties. Ruskin's were paid by public subscription, but Whistler was bankrupted within six months. The episode tarnished Ruskin's reputation, however, and may have accelerated his mental decline. It did nothing to mitigate Ruskin's consistently exaggerated sense of failure in persuading his readers to share in his own keenly felt priorities.

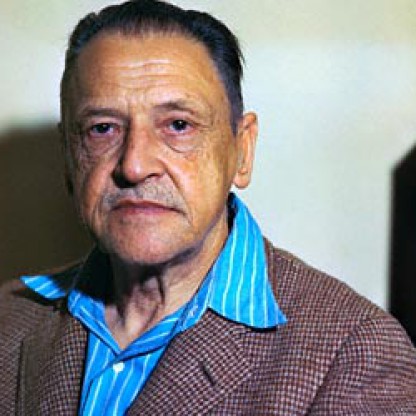

In middle age, and at his prime as a lecturer, Ruskin was described as slim, perhaps a little short, with an aquiline nose and brilliant, piercing blue eyes. Often sporting a double-breasted waistcoat, a high collar and, when necessary, a frock coat, he also wore his trademark blue neckcloth. From 1878 he cultivated an increasingly long beard, and took on the appearance of an "Old Testament" prophet.

In 1879, Ruskin resigned from Oxford, but resumed his Professorship in 1883, resigning again in 1884. He gave his reason as opposition to vivisection, but he had increasingly been in conflict with the University authorities, who refused to expand his Drawing School. He was also suffering increasingly poor health.

The period from the late 1880s was one of steady and inexorable decline. Gradually it became too difficult for him to travel to Europe. He suffered a complete collapse on his final tour, which included Beauvais, Sallanches and Venice, in 1888. The emergence and dominance of the Aesthetic movement and Impressionism distanced Ruskin from the modern art world, his ideas on the social utility of art contrasting with the "l'art pour l'art" or "art for art's sake" that was beginning to dominate. His later writings were increasingly seen as irrelevant, especially as he seemed to be more interested in book illustrators such as Kate Greenaway than in modern art. He also attacked Darwinian theory with increasing violence, although he knew and respected Darwin personally.

In 1884, the 17-year-old Beatrix Potter spotted Ruskin at the Royal Academy of Arts exhibition. She wrote in her journal, "Mr Ruskin was one of the most ridiculous figures I have seen. A very old hat, much necktie and aged coat buttoned up on his neck, humpbacked, not particularly clean looking. He had on high boots, and one of his trousers was tucked up on the top of one. He became aware of this half way round the room, and stood on one leg to put it right, but in doing so hitched up the other trouser worse than the first one had been."

His last great work was his autobiography, Praeterita (1885–89) (meaning, 'Of Past Things'), a highly personalised, selective, eloquent but incomplete account of aspects of his life, the preface of which was written in his childhood nursery at Herne Hill.

In a letter to his physician John Simon on 15 May 1886, Ruskin wrote:

A number of Utopian socialist Ruskin Colonies attempted to put his political ideals into practice. These communities included Ruskin, Florida, Ruskin, British Columbia and the Ruskin Commonwealth Association, a colony which existed in Dickson County, Tennessee from 1894 to 1899.

Although Ruskin’s 80th birthday was widely celebrated in 1899 (various Ruskin societies presenting him with a congratulatory address), Ruskin was scarcely aware of it. He died at Brantwood from influenza on 20 January 1900 at the age of 80. He was buried five days later in the churchyard at Coniston, according to his wishes. As he had grown weaker, suffering prolonged bouts of mental illness (thought in retrospect to have been CADASIL syndrome), he had been looked after by his second cousin, Joan(na) Severn (formerly "companion" to Ruskin's mother) and she inherited his estate. "Joanna's Care" was the eloquent final chapter of his memoir which he dedicated to her as a fitting tribute.

Ruskin wrote over 250 works, initially art criticism and history, but expanding to cover topics ranging over science, geology, ornithology, literary criticism, the environmental effects of pollution, mythology, travel, political economy and social reform. After his death Ruskin's works were collected in the 39-volume "Library Edition", completed in 1912 by his friends Edward Tyas Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. The range and quantity of Ruskin's writing, and its complex, allusive and associative method of expression, causes certain difficulties. In 1898, John A. Hobson observed that in attempting to summarise Ruskin's thought, and by extracting passages from across his work, "the spell of his eloquence is broken". Clive Wilmer has written, further, that "the anthologizing of short purple passages, removed from their intended contexts" is "something which Ruskin himself detested and which has bedevilled his reputation from the start". Nevertheless, some aspects of Ruskin's theory and criticism require further consideration.

The centenary of Ruskin's birth was keenly celebrated in 1919, but his reputation was already in decline and sank further in the fifty years that followed. The contents of Ruskin’s home were dispersed in a series of sales at auction, and Brantwood itself was bought in 1932 by the educationist and Ruskin enthusiast, collector and memorialist, John Howard Whitehouse. In 1934, it was opened to the public as a permanent memorial to Ruskin.

He was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century and up to the First World War. After a period of relative decline, his reputation has steadily improved since the 1960s with the publication of numerous academic studies of his work. Today, his ideas and concerns are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in environmentalism, sustainability and craft.

Ruskin was born at 54 Hunter Street, Brunswick Square, London (demolished 1969), south of St Pancras railway station. His childhood was characterised by the contrasting influences of his father and mother, both fiercely ambitious for him. John James Ruskin helped to develop his son's Romanticism. They shared a passion for the works of Byron, Shakespeare and especially Walter Scott. They visited Scott's home, Abbotsford in 1838, but Ruskin was disappointed by its appearance. Margaret Ruskin, an Evangelical Christian, more cautious and restrained than her husband, taught young John to read the King James Bible from beginning to end, and then to start all over again, committing large portions to memory. Its language, imagery and stories had a profound and lasting effect on his writing.

Since 2000, scholarly research has focused on aspects of Ruskin's legacy, including his impact on the sciences; John Lubbock and Oliver Lodge admired him. Two major academic projects have looked at Ruskin and cultural tourism (investigating, for Example, Ruskin's links with Thomas Cook); the other focuses on Ruskin and the theatre. The Sociologist and media theorist, David Gauntlett, argues that Ruskin's notions of craft can be traced to today's online community at YouTube and throughout Web 2.0. Similarly, architectural theorist Lars Spuybroek has argued that Ruskin's understanding of the Gothic as a combination of two types of variation, rough savageness and smooth changefulness, opens up a whole new way of thinking leading to digital and so-called parametric design.

Until 2005, biographies of both J. M. W. Turner and Ruskin had claimed that in 1858 Ruskin burned bundles of erotic paintings and drawings by Turner to protect Turner's posthumous reputation. Ruskin's friend Ralph Nicholson Wornum, who was Keeper of the National Gallery, was said to have colluded in the alleged destruction of Turner's works. In 2005, these works, which form part of the Turner Bequest held at Tate Britain, were re-appraised by Turner Curator Ian Warrell, who concluded that Ruskin and Wornum did not destroy them.

Notable modern-day Ruskin enthusiasts include the Writers Geoffrey Hill and Charles Tomlinson, and the politicians, Patrick Cormack, Frank Judd, Frank Field and Tony Benn. In 2006, Chris Smith, Baron Smith of Finsbury, Raficq Abdulla, Jonathon Porritt and Nicholas Wright were among those to contribute to the symposium, There is no wealth but life: Ruskin in the 21st Century. Jonathan Glancey at The Guardian and Andrew Hill at the Financial Times have both written about Ruskin, as has the broadcaster Melvyn Bragg.

Early in the 20th century, this statement appeared—without any authorship attribution—in magazine advertisements, in a Business catalogue, in student publications, and, occasionally, in editorial columns. Later in the 20th century, however, magazine advertisements, student publications, Business books, technical publications, and Business catalogues often included the statement with attribution to Ruskin.

Ruskin's strong rejection of Classical tradition in The Stones of Venice typifies the inextricable mix of aesthetics and morality in his thought: "Pagan in its origin, proud and unholy in its revival, paralysed in its old age... an architecture invented, as it seems, to make plagiarists of its Architects, slaves of its workmen, and sybarites of its inhabitants; an architecture in which intellect is idle, invention impossible, but in which all luxury is gratified and all insolence fortified." Rejection of mechanisation and standardisation informed Ruskin's theories of architecture, and his emphasis on the importance of the Medieval Gothic style. He praised the Gothic for what he saw as its reverence for nature and natural forms; the free, unfettered expression of artisans constructing and decorating buildings; and for the organic relationship he perceived between worker and guild, worker and community, worker and natural environment, and between worker and God. Attempts in the 19th century, to reproduce Gothic forms (such as pointed arches), attempts which he had helped to inspire, were not enough to make these buildings expressions of what Ruskin saw as true Gothic feeling, faith, and organicism.