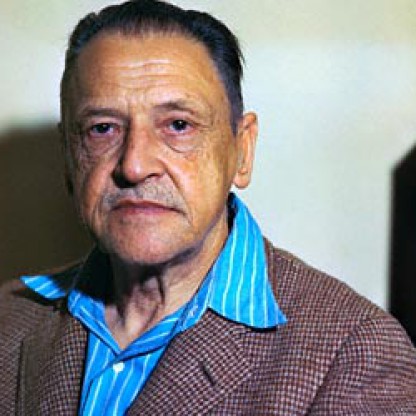

As per our current Database, Ezra Pound has been died on November 1, 1972.

When Ezra Pound die, Ezra Pound was 42 years old.

| Popular As | Ezra Pound |

| Occupation | Writers |

| Age | 42 years old |

| Zodiac Sign | Scorpio |

| Born | October 18, 1930 (Hailey, Idaho, United States, United States) |

| Birthday | October 18 |

| Town/City | Hailey, Idaho, United States, United States |

| Nationality | United States |

Ezra Pound’s zodiac sign is Scorpio. According to astrologers, Scorpio-born are passionate and assertive people. They are determined and decisive, and will research until they find out the truth. Scorpio is a great leader, always aware of the situation and also features prominently in resourcefulness. Scorpio is a Water sign and lives to experience and express emotions. Although emotions are very important for Scorpio, they manifest them differently than other water signs. In any case, you can be sure that the Scorpio will keep your secrets, whatever they may be.

Ezra Pound was born in the Year of the Horse. Those born under the Chinese Zodiac sign of the Horse love to roam free. They’re energetic, self-reliant, money-wise, and they enjoy traveling, love and intimacy. They’re great at seducing, sharp-witted, impatient and sometimes seen as a drifter. Compatible with Dog or Tiger.

I resolved that at thirty I would know more about poetry than any man living ... that I would know what was accounted poetry everywhere, what part of poetry was 'indestructible', what part could not be lost by translation and—scarcely less important—what effects were obtainable in one language only and were utterly incapable of being translated.

In this search I learned more or less of nine foreign languages, I read Oriental stuff in translations, I fought every University regulation and every professor who tried to make me learn anything except this, or who bothered me with "requirements for degrees".

Both parents' ancestors had emigrated from England in the 17th century. On his mother's side, Pound was descended from william Wadsworth (1594–1675), a Puritan who emigrated to Boston on the Lion in 1632. The Wadsworths married into the Westons of New York. Harding Weston and Mary Parker were the parents of Isabel Weston, Ezra's mother. Harding apparently spent most of his life without work, with his brother, Ezra Weston, and his brother's wife, Frances, looking after Mary and Isabel's needs.

On his father's side, the immigrant ancestor was John Pound, a Quaker, who arrived from England around 1650. Ezra's grandfather, Thaddeus Coleman Pound (1832–1914), was a Republican Congressman from North West Wisconsin who had made and lost a fortune in the lumber Business. Thaddeus's son Homer, Pound's father, worked for Thaddeus in the lumber Business until Thaddeus secured him the appointment as registrar of the Hailey land office. Homer and Isabel married the following year and Homer built a house in Hailey. Isabel was unhappy in Hailey and took Ezra with her to New York in 1887, when he was 18 months old. Homer followed them, and in 1889 he found a job as an assayer at the Philadelphia Mint. The family moved to Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, and in 1893 bought a six-bedroom house in Wyncote.

Pound was born in a small, two-story house in Hailey, Idaho Territory, the only child of Homer Loomis Pound (1858–1942) and Isabel Weston (1860–1948). His father had worked in Hailey since 1883 as registrar of the General Land Office.

Pound was also introduced to Sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Painter Wyndham Lewis and to the cream of London's literary circle, including the poet T. E. Hulme. The American heiress Margaret Lanier Cravens (1881–1912) became a patron; after knowing him a short time she offered a large annual sum to allow him to focus on his work. Cravens killed herself in 1912, after the Pianist Walter Rummel, long the object of her affection, married someone else. She may also have been discouraged by Pound's engagement to Dorothy.

Pound's education began in a series of dame schools, some of them run by Quakers: Miss Elliott's school in Jenkintown in 1892, the Heathcock family's Chelten Hills School in Wyncote in 1893, and the Florence Ridpath school from 1894, also in Wyncote. His first publication was on 7 November 1896 in the Jenkintown Times-Chronicle ("by E. L. Pound, Wyncote, aged 11 years"), a limerick about William Jennings Bryan, who had just lost the 1896 presidential election: "There was a young man from the West, / He did what he could for what he thought best; / But election came round, / He found himself drowned, / And the papers will tell you the rest."

Between 1897 and 1900 Pound attended Cheltenham Military Academy, sometimes as a boarder, where he specialized in Latin. The boys wore Civil War-style uniforms and besides Latin were taught English, history, arithmetic, marksmanship, military drilling and the importance of submitting to authority. Pound made his first trip overseas in mid-1898 when he was 13, a three-month tour of Europe with his mother and Frances Weston (Aunt Frank), who took him to England, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. After the academy he may have attended Cheltenham Township High School for one year, and in 1901, aged 15, he was admitted to the University of Pennsylvania's College of Liberal Arts.

It was at Pennsylvania in 1901 that Pound met Hilda Doolittle (later known as the poet H.D.), his first serious romance, according to Pound scholar Ira Nadel. In 1911 she followed Pound to London and became involved in developing the Imagism movement. Between 1905 and 1907 Pound wrote a number of poems for her, 25 of which he hand-bound and called Hilda's Book, and in 1908 he asked her father, the astronomy professor Charles Doolittle, for permission to marry her, but Doolittle dismissed Pound as a nomad. Pound was seeing two other women at the same time—Viola Baxter and Mary Moore—later dedicating a book of poetry, Personae (1909), to the latter. He asked Moore to marry him too, but she turned him down.

His parents and Frances Weston took Pound on another three-month European tour in 1902, after which he transferred, in 1903, to Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, possibly because of poor grades. Signed up for the Latin–Scientific course, he studied the Provençal dialect with william Pierce Shephard and Old English with Joseph D. Ibbotson; with Shephard he read Dante and from this began the idea for a long poem in three parts—of emotion, instruction and contemplation—planting the seeds for The Cantos. He wrote in 1913, in "How I Began":

Although Pound repudiated his antisemitism in public, he maintained his views in private. He refused to talk to Psychiatrists with Jewish-sounding names, dismissed people he disliked as "Jews", and urged visitors to read the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1903), a forgery claiming to represent a Jewish plan for world domination. He struck up a friendship with the conspiracy theorist and antisemite Eustace Mullins, believed to be associated with the Aryan League of America, and author of the 1961 biography This Difficult Individual, Ezra Pound.

Pound graduated from Hamilton College with a BPhil in 1905, then studied Romance languages under Hugo A. Rennert at the University of Pennsylvania, where he obtained an MA in early 1906 and registered to write a PhD thesis on the jesters in Lope de Vega's plays. A Harrison fellowship covered his tuition fees and gave him a travel grant of $500, which he used to return to Europe. Pound spent three weeks in Madrid in various libraries, including one in the royal palace. There, on 31 May 1906, he happened to be standing outside when the attempted assassination of King Alfonso took place, and Pound subsequently left the country for fear he would be identified with the anarchists. After Spain he spent two weeks in Paris, attending lectures at the Sorbonne, followed by a week in London.

From late 1907 Pound taught Romance languages at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana, a conservative town that he called "the sixth circle of hell". The equally conservative college dismissed him after he deliberately provoked the college authorities. Smoking was forbidden, but he would smoke cigarillos in his office down the corridor from the president's. He annoyed his landlords by entertaining friends, including women, and was forced out of one house after "[t]wo stewdents found me sharing my meagre repast with the lady–gent impersonator in my privut apartments", he told a friend.

Pound persuaded the bookseller Elkin Mathews to display A Lume Spento, and by October 1908 he was being discussed by the literati. In December he published a second collection, A Quinzaine for This Yule, and after the death of a lecturer at the Regent Street Polytechnic he managed to acquire a position lecturing in the evenings, from January to February 1909, on "The Development of Literature in Southern Europe". He would spend his mornings in the British Museum Reading Room, then lunch at the Vienna Café on Oxford Street. Ford Madox Ford wrote:

In June 1909 the Personae collection became the first of Pound's works to have any commercial success. It was favorably reviewed; one review said it was "full of human passion and natural magic". Rupert Brooke was unimpressed, complaining that Pound had fallen under the influence of Walt Whitman, writing in "unmetrical sprawling lengths". In September a further 27 poems appeared as Exultations. Around the same time Pound moved into new rooms at Church Walk, off Kensington High Street, where he lived most of the time until 1914.

In June 1910 Pound returned to the United States for eight months; his arrival coincided with the publication of his first book of literary criticism, The Spirit of Romance, based on his lecture notes at the polytechnic. His essays on America were written during this period, compiled as Patria Mia and not published until 1950. He loved New York but felt the city was threatened by commercialism and vulgarity, and he no longer felt at home there. He found the New York Public Library, then being built, especially offensive and, according to Paul L. Montgomery, visited the architects' offices almost every day to shout at them.

Hilda Doolittle arrived in London from Philadelphia in May 1911 with the poet Frances Gregg and Gregg's mother; when they returned in September, Doolittle decided to stay on. Pound introduced her to his friends, including the poet Richard Aldington, whom she would marry in 1913. Before that the three of them lived in Church Walk, Kensington—Pound at no. 10, Doolittle at no. 6, and Aldington at no. 8—and worked daily in the British Museum Reading Room.

Ripostes, published in October 1912, begins Pound's shift toward minimalist language. Michael Alexander describes the poems as showing a greater concentration of meaning and economy of rhythm than his earlier work. It was published when Pound had just begun his move toward Imagism; his first use of the word Imagiste appears in his prefatory note to the volume. The collection includes five poems by Hulme and a translation of the 8th-century Old English poem The Seafarer, although not a literal translation. It upset scholars, as would Pound's other translations from Latin, Italian, French and Chinese, either because of errors or because he lacked familiarity with the cultural context. Alexander writes that in some circles, Pound's translations made him more unpopular than the treason charge, and the reaction to The Seafarer was a rehearsal for the negative response to Homage to Sextus Propertius in 1919. His translation from the Italian of Sonnets and ballate of Guido Cavalcanti was also published in 1912.

Pound was fascinated by the translations of Japanese poetry and Noh plays which he discovered in the papers of Ernest Fenollosa, an American professor who had taught in Japan. Fenollosa had studied Chinese poetry under Japanese scholars; in 1913 his widow, Mary McNeil Fenollosa, decided to give his unpublished notes to Pound after seeing his work; she was looking for someone who cared about poetry rather than philology. Pound edited and published Fenellosa's The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry in 1918.

Between 1914 and 1916 Pound assisted in the serialisation of James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in The Egoist, then helped to have it published in book form. In 1915 he persuaded Poetry to publish T. S. Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock". Eliot had sent "Prufrock" to almost every Editor in England, but was rejected. He eventually sent it to Pound, who instantly saw it as a work of genius and submitted it to Poetry. "[Eliot] has actually trained himself AND modernized himself ON HIS OWN", Pound wrote to Monroe in October 1914. "The rest of the promising young have done one or the other but never both. Most of the swine have done neither."

Pound was deeply affected by the war. He was devastated when Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, from whom he had commissioned a sculpture of himself two years earlier, was killed in the trenches in 1915. He published Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir the following year, in reaction to what he saw as an unnecessary loss. In the autumn of 1917 his depression worsened. He blamed American provincialism for the seizure of the October issue of The Little Review. The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice applied the Comstock Laws against an article Lewis wrote, describing it as lewd and indecent. Around the same time, Hulme was killed by shell-fire in Flanders, and Yeats married Georgie Hyde-Lees. In 1918, after a bout of illness which was presumably the Spanish influenza, Pound decided to stop writing for The Little Review, mostly because of the volume of work. He asked the publisher for a raise to hire 23-year-old Iseult Gonne as a typist, causing rumors that Pound was having an affair with her, but he was turned down.

Pound helped advance the careers of some of the best-known modernist Writers of the early 20th century. In addition to Eliot, Joyce, Lewis, Frost, Williams, Hemingway and Conrad Aiken, he befriended and helped Marianne Moore, Louis Zukofsky, Jacob Epstein, Basil Bunting, E.E. Cummings, Margaret Anderson, George Oppen and Charles Olson. Hugh Witemeyer argues that the Imagist movement was the most important in 20th-century English-language poetry because it affected all the leading poets of Pound's generation and the two generations after him. In 1917 Carl Sandburg wrote in Poetry: "All talk on modern poetry, by people who know, ends with dragging in Ezra Pound somewhere. He may be named only to be cursed as wanton and mocker, poseur, trifler and vagrant. Or he may be classed as filling a niche today like that of Keats in a preceding epoch. The point is, he will be mentioned."

In 1919 he published a collection of his essays for The Little Review as Instigations, and in the March 1919 issue Poetry, he published Poems from the Propertius Series, which appeared to be a translation of the Latin Poet Sextus Propertius. When he included this in his next poetry collection in 1921, he had renamed it Homage to Sextus Propertius in response to criticism of his translation skills. "Propertius" is not a strict translation; biographer David Moody describes it as "the refraction of an ancient poet through a modern intelligence". Harriet Monroe, Editor of Poetry, published a letter from a professor of Latin, W. G. Hale, saying that Pound was "incredibly ignorant" of the language, and alluded to "about three-score errors" in Homage. Monroe did not publish Pound's response, which began "Cat-piss and porcupines!!" and continued, "The thing is no more a translation than my 'Altaforte' is a translation, or than Fitzgerald's Omar is a translation". Moore interpreted Pound's silence after that as his resignation as foreign Editor.

The war had shattered Pound's belief in modern western civilization. He saw the Vorticist movement as finished and doubted his own Future as a poet. He had only the New Age to write for; his relationship with Poetry was finished, The Egoist was quickly running out of money because of censorship problems caused by the serialization of Joyce's Ulysses, and the funds for The Little Review had dried up. Other magazines ignored his submissions or refused to review his work. Toward the end of 1920 he and Dorothy decided their time in London was over and resolved to move to Paris.

The Pounds settled in Paris in January 1921, and several months later moved into an inexpensive apartment at 70 bis Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs. Pound became friendly with Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Fernand Léger and others of the Dada and Surrealist movements, as well as Basil Bunting, Ernest Hemingway and his wife, Hadley Richardson. He spent most of his time building furniture for his apartment and bookshelves for the bookstore Shakespeare and Company, and in 1921 the volume Poems 1918–1921 was published. In 1922 Eliot sent him the manuscript of The Waste Land, then arrived in Paris to edit it with Pound, who blue-inked the manuscript with comments like "make up yr. mind ..." and "georgian". Eliot wrote: "I should like to think that the manuscript, with the suppressed passages, had disappeared irrecoverably; yet, on the other hand, I should wish the blue pencilling on it to be preserved as irrefutable evidence of Pound's critical genius."

In 1922 the literary critic Edmund Wilson reviewed Pound's latest published volume of poetry, Poems 1918–21, and took the opportunity to provide an overview of his estimation of Pound as poet. In his essay on Pound, titled "Ezra Pound's Patchwork", Wilson wrote:

Hemingway asked Pound to blue-ink his short stories. Although Hemingway was 14 years younger, the two forged a lifelong relationship of mutual respect and friendship, living on the same street for a time, and touring Italy together in 1923. "They liked each other personally, shared the same aesthetic aims, and admired each other's work", writes Hemingway biographer Jeffrey Meyers, with Hemingway assuming the status of pupil to Pound's teaching. Pound introduced Hemingway to Lewis, Ford, and Joyce, while Hemingway in turn tried to teach Pound to box, but as he told Sherwood Anderson, "[Ezra] habitually leads with his chin and has the general grace of a crayfish or crawfish".

In 1924 Pound secured funding for Ford Madox Ford's The Transatlantic Review from American attorney John Quinn. The Review published works by Pound, Hemingway and Gertrude Stein, as well as extracts from Joyce's Finnegans Wake, before the money ran out in 1925. It also published several Pound music reviews, later collected into Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony.

In 1925 the literary magazine This Quarter dedicated its first issue to Pound, including tributes from Hemingway and Joyce. Pound published Cantos XVII–XIX in the winter editions. In March 1927 he launched his own literary magazine, The Exile, but only four issues were published. It did well in the first year, with contributions from Hemingway, E. E. Cummings, Basil Bunting, Yeats, William Carlos Williams and Robert McAlmon; some of the poorest work in the magazine were Pound's rambling editorials on Confucianism and or in praise of Lenin, according to biographer J. J. Wilhelm. He continued to work on Fenollosa's manuscripts, and in 1928 won The Dial's poetry award for his translation of the Confucian classic Great Learning (Dà Xué, transliterated as Ta Hio). That year his parents Homer and Isabel visited him in Rapallo, seeing him for the first time since 1914. By then Homer had retired, so they decided to move to Rapallo themselves. They took a small house, Villa Raggio, on a hill above the town.

Pound wrote intensively about economic theory with the ABC of Economics and Jefferson and/or Mussolini, published in the mid-1930s right after he was introduced to Mussolini. These were followed by The Guide to Kulchur, covering 2500 years of history, which Tim Redman describes as the "most complete synthesis of Pound's political and economic thought". Pound thought writing the cantos meant writing an epic about history and economics, and he wove his economic theories throughout; neither can be understood without the other. In these pamphlets and in The ABC of Reading, he sought to emphasize the value of art and to "aestheticize the political", written forcefully, according to Nadel, and in a "determined voice". In form his criticism and essays are direct, repetitive and reductionist, his rhetoric minimalist, filled with "strident impatience", according to Pound scholar Jason Coats, and frequently failing to make a coherent claim. He rejected traditional rhetoric and created his own, although not very successfully, in Coats's view.

Pound came to believe that the cause of World War I was Finance capitalism, which he called "usury", that the solution lay in C.H. Douglas's idea of social credit, and that fascism was the vehicle for reform. He had met Douglas in the New Age offices and had been impressed by his ideas. He gave a series of lectures on economics, and made contact with politicians in the United States to discuss education, interstate commerce and international affairs. Although Hemingway advised against it, on 30 January 1933 Pound met Benito Mussolini. Olga Rudge played for Mussolini and told him about Pound, who had earlier sent him a copy of Cantos XXX. During the meeting Pound tried to present Mussolini with a digest of his economic ideas, but Mussolini brushed them aside, though he called the Cantos "divertente" (entertaining). The meeting was recorded in Canto XLI: "'Ma questo' / said the boss, 'è divertente.'" Pound said he had "never met anyone who seemed to get my ideas so quickly as the boss".

Pound broadcast over Rome Radio, although the Italian government was at first reluctant, concerned that he might be a double agent. He told a friend: "It took me, I think it was, two years, insistence and wrangling etc., to get hold of their microphone." He recorded over a hundred broadcasts criticizing the United States, Roosevelt, Roosevelt's family and the Jews, and rambling about his poetry, economics and Chinese philosophy. The first was in January 1935, and by February 1940 he was broadcasting regularly; he traveled to Rome one week a month to pre-record the 10-minute broadcasts, for which he was paid around $17, and they were broadcast every three days. The broadcasts required the Italian government's approval, although he often changed the text in the studio. Tytell wrote that Pound's voice had assumed a "rasping, buzzing quality like the sound of a hornet stuck in a jar", that throughout the "disordered rhetoric of the talks he sustained the notes of chaos, hysteria, and exacerbated outrage." The politics apart, Pound needed the money; his father's pension payments had stopped —his father died in February 1942 in Rapallo — and Pound had his mother and Dorothy to look after.

When Olivia Shakespear died in October 1938 in London, Dorothy asked Pound to organize the funeral, where he saw their 12-year-old son Omar for the first time in eight years. He visited Eliot and Wyndham Lewis, who produced a now-famous portrait of Pound reclining. In April 1939 he sailed for New York, believing he could stop America's involvement in World War II, happy to answer reporters' questions about Mussolini while he lounged on the deck of the ship in a tweed jacket. He traveled to Washington, D.C., where he met senators and congressmen. His daughter, Mary, said that he had acted out of a sense of responsibility, rather than megalomania; he was offered no encouragement, and was left feeling depressed and frustrated.

In June 1939 he received an honorary doctorate from Hamilton College, and a week later returned to Italy from the States and began writing antisemitic material for Italian newspapers. He wrote to James Laughlin that Roosevelt represented Jewry, and signed the letter with "Heil Hitler". He started writing for Action, a newspaper owned by the British fascist Sir Oswald Mosley, arguing that the Third Reich was the "natural civilizer of Russia". After war broke out in September that year, he began a furious letter-writing campaign to the politicians he had petitioned six months earlier, arguing that the war was the result of an international banking conspiracy and that the United States should keep out of it.

Tytell writes that, by the 1940s, no American or English poet had been so active politically since William Blake. Pound wrote over a thousand letters a year during the 1930s and presented his ideas in hundreds of articles, as well as in The Cantos. His greatest fear was an economic structure dependent on the armaments industry, where the profit motive would govern war and peace. He read George Santayana and The Law of Civilization and Decay by Brooks Adams, finding confirmation of the danger of the capitalist and usurer becoming dominant. He wrote in The Japan Times that "Democracy is now currently defined in Europe as a 'country run by Jews,'" and told Sir Oswald Mosley's newspaper that the English were a slave race governed since Waterloo by the Rothschilds.

The war years threw Pound's domestic arrangements into disarray. Olga lost possession of her house in Venice and took a small house with Mary above Rapallo at Sant' Ambrogio. In 1943 Pound and Dorothy were evacuated from their apartment in Rapallo. His mother's apartment was too small, and the couple moved in with Olga. Mary, then 19 and finished with convent school, was quickly sent back to Gais in Switzerland, leaving Pound, as she would later write, "pent up with two women who loved him, whom he loved, and who coldly hated each other."

On 15 November 1945 Pound was transferred to the United States. An escorting officer's impression was that "he is an intellectual 'crackpot' who imagined that he could correct all the economic ills of the world and who resented the fact that ordinary mortals were not sufficiently intelligent to understand his aims and motives." He was arraigned in Washington, D.C., on the 25th of that month on charges of treason. The charges included broadcasting for the enemy, attempting to persuade American citizens to undermine government support of the war, and strengthening morale in Italy against the United States.

Pound's Lawyer, Julien Cornell, whose efforts to have him declared insane are credited with having saved him from life imprisonment, requested his release at a bail hearing in January 1947. The hospital's superintendent, Winfred Overholser, agreed instead to move him to the more pleasant surroundings of Chestnut Ward, close to Overholser's private quarters, which is where he spent the next 12 years. The Historian Stanley Kutler was given access in the 1980s to military intelligence and other government documents about Pound, including his hospital records, and wrote that the Psychiatrists believed Pound had a narcissistic personality, but they considered him sane. Kutler believes that Overholser protected Pound from the Criminal justice system because he was fascinated by him.

The awards committee consisted of 15 fellows of the Library of Congress, including several of Pound's supporters, such as Eliot, Tate, Conrad Aiken, Amy Lowell, Katherine Anne Porter and Theodore Spencer. The idea was that the Justice Department would be placed in an untenable position if Pound won a major award and was not released. Laughlin published The Pisan Cantos on 30 July 1948, and the following year the prize went to Pound. There were two dissenting voices, Francis Biddle's wife, Katherine Garrison Chapin, and Karl Shapiro, who said that he could not vote for an antisemite because he was Jewish himself. Pound responded to the award with "No comment from the bughouse."

The rise of New Criticism during the 1950s, in which author is separated from text, secured Pound's poetic reputation. Nadel writes that the publication of T.S. Eliot's Literary Essays in 1954 "initiated the recuperation of Ezra Pound". Eliot's essays coincided with the work of Hugh Kenner, who visited Pound extensively at St. Elizabeths. Kenner wrote that there was no great contemporary Writer less read than Pound, adding that there is also no one to appeal more through "sheer beauty of language". Along with Donald Davie, Kenner brought a new appreciation to Pound's work in the 1960s and 1970s. Donald Gallup's Pound bibliography was published in 1963 and Kenner's The Pound Era in 1971. In the 1970s a literary journal dedicated to Pound studies (Paideuma) was established, and Ronald Bush published the first dedicated critical study of The Cantos, to be followed by a number of research editions of The Cantos.

Tytell writes that Pound was in his element in Chestnut Ward. He was at last provided for, and was allowed to read, write and receive visitors, including Dorothy for several hours a day. He took over a small alcove with wicker chairs just outside his room, and turned it into his private living room, where he entertained his friends and important literary figures. He began work on his translation of Sophocles's Women of Trachis and Electra, and continued work on The Cantos. It reached the point where he refused to discuss any attempt to have him released. Olga Rudge visited him twice, once in 1952 and again in 1955, and was unable to convince him to be more assertive about his release. She wrote to a friend: "E.P. has—as he had before—bats in the belfry but it strikes me that he has fewer not more than before his incarceration."

Pound's friends continued to try to get him out. Shortly after Hemingway won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954, he told Time magazine that "this would be a good year to release poets". The poet Archibald Macleish asked Hemingway in June 1957 to write a letter on Pound's behalf. Hemingway believed Pound was unable to abstain from awkward political statements or from friendships with people like Kasper, but he signed a letter of support anyway and pledged $1,500 to be given to Pound when he was released. In an interview for the Paris Review in early 1958, Hemingway said that Kasper should be jailed and Pound released. Kasper was eventually jailed, for inciting a riot in connection with the Hattie Cotton School in Nashville, targeted because a black girl had registered as a student. He was also questioned relating to the bombing of the school.

Pound arrived in Naples in July 1958, where he was photographed giving a fascist salute to the waiting press. When asked when he had been released from the mental hospital, he replied: "I never was. When I left the hospital I was still in America, and all America is an insane asylum." He and Dorothy went to live with Mary at Castle Brunnenburg, near Merano in the Province of South Tyrol, where he met his grandson, Walter, and his granddaughter, Patrizia, for the first time, then returned to Rapallo, where Olga Rudge was waiting to join them.

By December 1959 Pound was mired in depression. He saw his work as worthless and The Cantos botched. In a 1960 interview given in Rome to Donald Hall for Paris Review, he said: "You—find me—in fragments." Hall wrote that he seemed in an "abject despair, accidie, meaninglessness, abulia, waste". He paced up and down during the three days it took to complete the interview, never finishing a sentence, bursting with Energy one minute, then suddenly sagging, and at one point seemed about to collapse. Hall said it was clear that he "doubted the value of everything he had done in his life."

Those close to him thought he was suffering from dementia, and in mid-1960 Mary placed him in a clinic near Merano when his weight dropped. He picked up again, but by early 1961 he had a urinary infection. Dorothy felt unable to look after him, so he went to live with Olga in Rapallo, then Venice; Dorothy mostly stayed in London after that with Omar. Pound attended a neo-Fascist May Day parade in 1962, but his health continued to decline. The following year he told an interviewer, Grazia Levi: "I spoil everything I touch. I have always blundered ... All my life I believed I knew nothing, yes, knew nothing. And so words became devoid of meaning."

William Carlos Williams died in 1963, followed by Eliot in 1965. Pound went to Eliot's funeral in London and on to Dublin to visit Yeats's widow. Two years later he went to New York where he attended the opening of an exhibition featuring his blue-inked version of Eliot's The Waste Land. He went on to Hamilton College where he received a standing ovation.

Later in his life, Pound analyzed what he judged to be his own failings as a Writer attributable to his adherence to ideological fallacies. Allen Ginsberg states that, in a private conversation in 1967, Pound told the young poet, "my poems don't make sense." He went on to say that he "was not a lunatic, but a moron", and to characterize his writing as "stupid and ignorant", "a mess". Ginsberg reassured Pound that he "had shown us the way", but Pound refused to be mollified:

Following Mullins' biography, described by Nadel as "partisan" and "melodramatic", was Noel Stock's factual 1970 Life of Ezra Pound, although the material included was subject to Dorothy's approval. The 1980s saw three significant biographies: John Tytell's "neutral" account in 1987, followed by Wilhelm's multi-volume biography. Humphrey Carpenter's sprawling narrative, a "complete life", built on what Stock began; unlike Stock, Carpenter had the benefit of working without intervention from Pound's relatives. In 2007 David Moody published the first of his multi-volume biography, combining narrative with literary criticism, the first work to link the two.

On his 87th birthday, 30 October 1972, he was too weak to leave his bedroom. The next night he was admitted to the Civil Hospital of Venice, where he died in his sleep of an intestinal blockage on 1 November, with Olga at his side. Dorothy was unable to travel to the funeral. Four gondoliers dressed in black rowed the body to the island cemetery, Isola di San Michele, where he was buried near Diaghilev and Stravinsky. Dorothy died in England the following year. Olga died in 1996 and was buried next to Pound.

The outrage after Pound's wartime collaboration with Mussolini's regime was so deep that the imagined method of his execution dominated the discussion. Arthur Miller considered him worse than Hitler: "In his wildest moments of human vilification Hitler never approached our Ezra ... he knew all America's weaknesses and he played them as expertly as Goebbels ever did." The response went so far as to denounce all modernists as fascists, and it was only in the 1980s that critics began a re-evaluation. Macha Rosenthal wrote that it was "as if all the beautiful vitality and all the brilliant rottenness of our heritage in its luxuriant variety were both at once made manifest" in Ezra Pound.

Nadel's 2010 Pound in Context is a contextual literary approach to Pound scholarship. Pound's life, "the social, political, historical, and literary developments of his period", is fully investigated, which, according to Nadel is "the grid for reading Pound's poetry." In 2012 Matthew Feldman wrote that the more than 1,500 documents in the "Pound files" held by the FBI have been ignored by scholars, and almost certainly contain evidence that "Pound was politically cannier, was more bureaucratically involved with Italian Fascism, and was more involved with Mussolini's regime than has been posited".

James Laughlin had "Cantos LXXIV–LXXXIV" ready for publication in 1946 under the title The Pisan Cantos, and gave Pound an advance copy, but he held back, waiting for an appropriate time to publish. A group of Pound's friends—Eliot, Cummings, W. H. Auden, Allen Tate, and Julien Cornell—met Laughlin to discuss how to get him released. They planned to have Pound awarded the first Bollingen Prize, a new national poetry award by the Library of Congress, with $1,000 prize money donated by the Mellon family.

Pound's literary criticism and essays are, according to Massimo Bacigalupo, a "form of intellectual journal". In early works, such as The Spirit of Romance and "I Gather the Limbs of Osiris", Pound paid attention to medieval troubadour poets—Arnaut Daniel and François Villon. The former piece was to "remain one of Pound's principal sourcebooks for his poetry"; in the latter he introduces the concept of "luminous details". The leitmotifs in Pound's literary criticism are recurrent patterns found in historical events, which, he believed, through the use of judicious juxtapositions Illuminate truth; and in them he reveals forgotten Writers and cultures.

The Cantos is difficult to decipher. In the epic poem, Pound disregards literary genres, mixing satire, hymns, elegies, essays and memoirs. Pound scholar Rebecca Beasley believes it amounts to a rejection of the 19th-century nationalistic approach in favor of early-20th-century comparative literature. Pound reaches across cultures and time periods, assembling and juxtaposing "themes and history" from Homer to Ovid and Dante, from Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, and many others. The work presents a multitude of protagonists as "travellers between nations". The nature of The Cantos, she says, is to compare and measure among historical periods and cultures and against "a Poundian standard" of modernism.